One of GCW’s guests memoirs of a river trip was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, it’s a great read!

Westward ho boy!

A couple of Eastern city slickers get their raft and tent on at the Grand Canyon, rapidly crafting camaraderie.

By Phil Goldsmith, For The Inquirer

POSTED: July 07, 2014

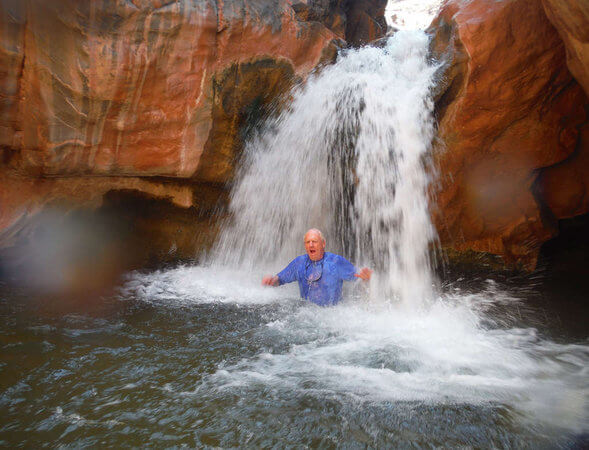

Phil Goldsmith gets a natural shower at the Grand Canyon. “For seven days we were at the bottom looking up, shooting the rapids, sleeping under the stars, hiking in the crevices of the canyons, discovering hidden waterfalls, eating our meals on the river’s banks, and making new friends.” (Courtesy Phil Goldsmith)

Camping, like planning, is not our forte. The only time we went camping was three decades ago with a group of friends. They were experienced campers; we weren’t. They knew enough to bring utensils. We did not, though we did bring our own hair dryers. This time, I assured Essie we wouldn’t have to do much work, just sit on the raft and watch the scenery. After all, Iris and Howard had stayed at five-star hotels when they went on African safaris. I was sure someone would be carrying our stuff.

I was wrong.

Not only did we have to carry our own bags, we also had to set up our own tents and cots and disassemble them each day.

I was not a happy camper. Manual labor isn’t my thing.

Had I known all this beforehand, I would have declined Iris’ invitation and sent her a birthday card instead.

And I would have missed one of the best trips of my life.

There are 16 commercial rafting companies that are licensed by the National Park Service to take visitors down the Colorado River. Iris opted for Grand Canyon Whitewater and its seven-day, 187-mile motorized trip.

Teddy Roosevelt, who declared the Grand Canyon a national monument in 1908, said it is “the one great sight which every American should see.” And 4.5 million visitors do just that every year, but only 27,000 do so by river. I realized there is a big difference between staring down at the glorious chasm from the South Rim and being at the bottom looking up. It’s the difference between being a spectator and, as TR would say, being in the “arena.” And by looking up at nature’s awe-inspiring treasure, a billion years in the making, you are humbled by just how infinitesimal we are in the overall scheme of things.

For seven days we were at the bottom looking up, shooting the rapids, sleeping under the stars, hiking in the crevices of the canyons, discovering hidden waterfalls, eating our meals on the river’s banks, and making new friends.

Our adventure began on May 11, at Lee’s Ferry, a gateway for rafting through the Grand Canyon. There we met for the first time the 24 people who would be with us for the week, sharing two 14-passenger rafts, each equipped with a 30-horsepower outboard motor.

We were the only Easterners, the city slickers. Except for a couple from Wales, the rest were from the West – Washington, Nebraska, Montana, and California. Ages ranged from the early 30s to early 70s, about a third were retired. Occupations ran the gamut: a fireman, teachers, nurses, a psychologist, an accountant, a hedge fund salesman, a management consultant, a farmer, a human resources administrator, a civil engineer, and a Boeing employee who specialized in installing the left wing on all its new 737s.

Also joining us were our two guides, or river runners, as they are called: Brock, with his calming, self-assured manner, and Brie, one of the few women pilots on the Colorado River, and their two helpers, Stolf and Easy.

Their main task was to guide us safely through more than 80 rapids that we would traverse during the week. Like children at an amusement park, we screamed as we headed down some of the steeper rapids, like Hance Rapid with its 30-foot drop – not so much out of fear as from the frigid 50-degree river water that would suddenly slap us in the face.

Quickly a routine developed. By late morning we would pull ashore and have lunch, take a hike, or, as we did one afternoon, float on the Little Colorado River on our backs down one of the tamer rapids before regrouping to continue our journey.

By late afternoon, we would call it quits and find a place to set up camp. Then the work began: setting up our tents and cots. You could readily tell the Easterners from the Westerners.

By the time we, the city slickers, figured out which pole went into which hole, the Westerners were already done, relaxing by the river sipping wine or drinking beer. Howard and I had a good laugh as we struggled. My wife, on the other hand, was not a bit amused. As someone whose father had made his living with his hands, she glared at me with such disdain she might just as well have been wearing a neon sign that asked “How did I marry this klutz?”

Fortunately the Westerners came to our rescue, making order out of our disorder. And soon we were all enjoying our staff-cooked dinners – pork chops, lasagna, steak, salmon. After dinner, we gathered in a circle as the sun set and Brock told a story or recited some poetry.

With flashlights in hand, we then made our way back to our tents, hoping we could find the right one; in darkness they were as indistinguishable as Philadelphia rowhouses.

By 6 a.m., with the sun still hidden behind the pink-colored rocks and the moon still visible above, we would hear, “Coffee is ready!” Another day was beginning, which meant that after breakfast, everyone scurried to take down their tents, disassemble the cots, pack their bags, and load them on the rafts so we could hit the river by 8.

Need I say who would be the last ones to the rafts?

I was in awe of the history and geology of this most sacred space, but it was the people themselves who captured my attention and, frankly, rejuvenated my faith in humanity.

I was in the midst of reading a book called Give and Take by Adam Grant, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, and I realized I was surrounded on this trip by the giver-type he described in his book. They pitched in to help us with our tents and cots. They helped carry our bags or guide us as we navigated some of the steeper rocks on our hikes. They helped each other. No quid pro quos.

Quickly, we became a community. There were no airs or one-upmanship. No rank or sense of importance. No fancy clothes. Or even hair dryers. Hygiene basically consisted of brushing your teeth. We shared the same non-flushable unisex toilet, affectionately called the “Groover.” With no Internet, there were no distractions of e-mails, texts, or phone calls. Never once did we talk about politics or religion.

I must report, however, that I did find one vestige of personal pride and privacy hard to shake. At the very end of the trip, when we were about to be helicoptered out of the canyon to the North Rim, Garth, the dispatcher at the helipad, needed to know how much you weighed so he could determine where you sat in the chopper to ensure its balance. The women tiptoed up to Garth and whispered the magic number in his ear. Their need to guard this fact from the rest of us after a week of little privacy was as much a mystery to me as the geological formation of the Grand Canyon.

———-

Phil Goldsmith is a former managing director of the City of Philadelphia who fortunately had lots of help to get things done.